What is FoundationDB?

I'm a total digital hoarder. If I find interesting articles, papers, or other things, I immediately find myself burying them in my computer disk's dungeons. Fortunately, I've gathered my motivation to start reading and scrutinising them for a while.

The main motivation is to understand the nuances of concepts and systems. If you are passionate about your profession sometimes you would like to see the dungeons of the Misty Mountains as a mortal(please don't mention human greediness this is not the topic!) even if your purpose is not earning a single cent.

My journey is going to be to find a new perspective or details of magnificence and my blog will be the shadows reflecting my lens. :)

After this brief disclaimer! Let's start.

FoundationDB is a key-value database solution, or is it something more? What is the difference between FoundationDB and others?

Core Specifications

FoundationDB is a highly customizable multi-model (not only KV) data store, which means if you use it as a DB engine, you can build your query, schema, and data models on top of it, keeping it as a KV under the hood.

It is really easy to use. You can download and run it. What are the specifications?

Strict Serializable: It means you can run a fully ACID-compliant KV store.

Fault Tolerant: For example, if the database crashes, the restart time, according to Apple engineers, is usually less than ~5 seconds in production. This is impressive considering Apple's scale. [5.3 Reconfiguration Duration, 6.3 Fast Recovery]

Fail fast and recover fast. To improve availability, FDB strives to minimize Mean-Time-To-Recovery (MTTR), which includes the time to detect a failure, proactively shut down the transaction management system, and recover. In our production clusters, the total time is usually less than five seconds.

Architecture

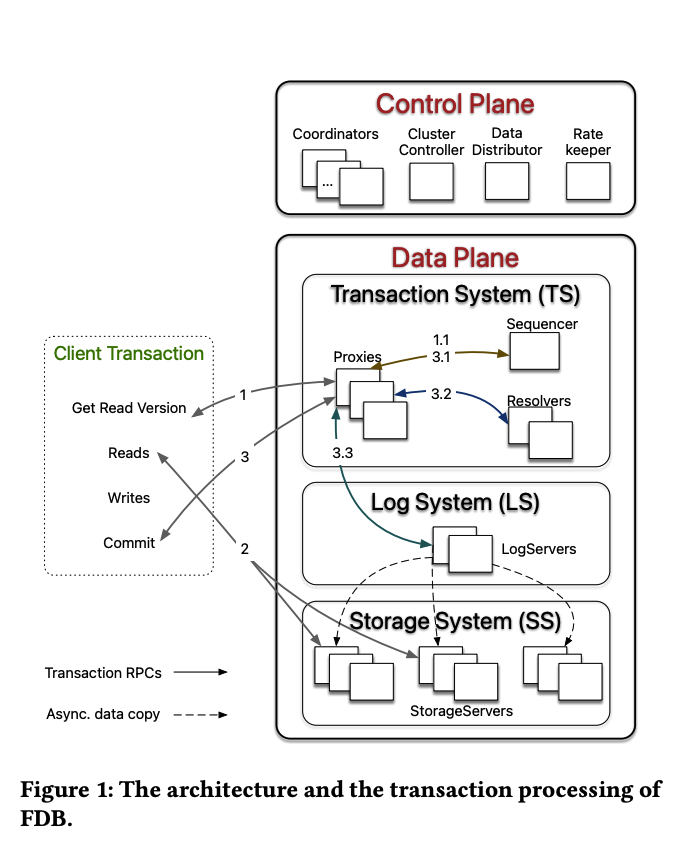

It utilizes an "Unbundled Architecture." The system is fundamentally divided into two main layers: Control Plane and Data Plane.

Control Plane

The Control Plane has different components that are responsible for different tasks:

- Storing metadata (configuration, system details, etc.) of the entire database

- Managing central time

- Checking the health of other components

Data Plane

The Data Plane has different components:

- Transaction System (TS): Proxies, Sequencer, Resolvers. It is memory-intensive.

- Log System (LS): Append-only WAL.

- Storage System (SS): Solely responsible for the persistence layer.

The Transaction Journey

Roles

- Proxies: Act as a bridge between the Client and the System.

- Sequencer: It manages and assigns the Read Version and Write Version.

There is a Global Monotonic Version Generator; to simplify, the sequencer keeps monotonically and sequentially assigning a number to every transaction. This naturally orders every transaction from a single point.

Step-by-Step Request

When a transaction starts, the client requests a Read Version from the Proxy (the Proxy gets it from the Sequencer). The client keeps this RV until COMMIT time. Then, the client sends a COMMIT request to the Proxy, and the Proxy obtains a Commit Version from the Sequencer for this transaction.

Let's have a look at one request journey. The first transaction request is received by the proxy and takes read version 100 (Snapshot Isolation, MVCC). The client does not care what happened after RV{100} until it attempts to commit the transaction.

This transaction sees its own uncommitted changes (850).

BEGIN TRANSACTION; -- read version 100

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id=1;

-- balance result is 1000

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 150 WHERE id = 1;

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id=1;

-- balance result is 850

-- COMMIT;

This transaction started after the first transaction but committed before.

BEGIN TRANSACTION; -- read version 101

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 100 WHERE id = 1;

COMMIT; -- commit version 103

So far, the changes do not go to the proxy server; they are buffered in the Client Memory Buffer !

An FDB transaction observes and modifies a snapshot of the database at a certain version and changes are applied to the underlying database only when the transaction commits. A transaction’s writes (i.e., set() and clear() calls) are buffered by the FDB client until the final commit() call.

Commit Step

- The client sends a commit request to the Proxy.

- The Proxy requests a new Commit version CV{110} from the Sequencer.

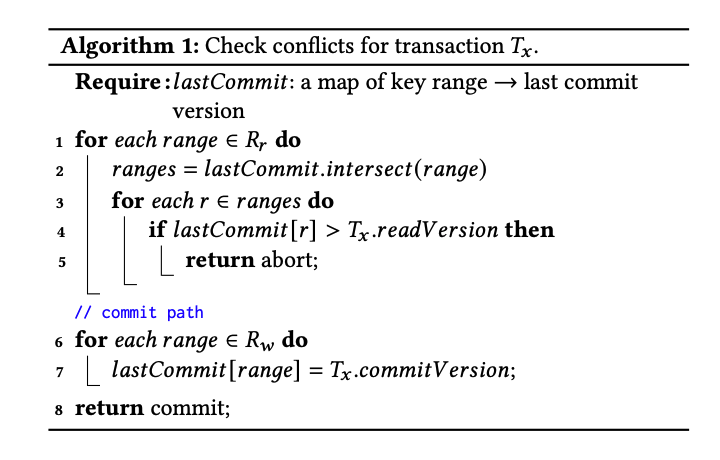

- Resolvers: Conflict agents. Check for modifications: "Has the data been modified during a transaction?"

Resolvers compare RV{100} - CV{110}. Has the account balance changed so far?

- NO: SUCCESS! account balance is 850 after version 110.

- YES: CONFLICT! Another transaction had updated the account balance to 900.

Optimistic concurrency control (OCC) does not lock but reads before commit, then reverts changes. The client retries the same request with a newer read version.

A successful transaction directly goes to the Log Server and, once the durability quorum is met (written to chosen min tlogs), an ACK is returned to the client.

Conflict Check Algorithm

Here is the official algorithm for the conflict check:

Storage and Logs

Storage Servers (SS): Work on SQLite or the Redwood engine.

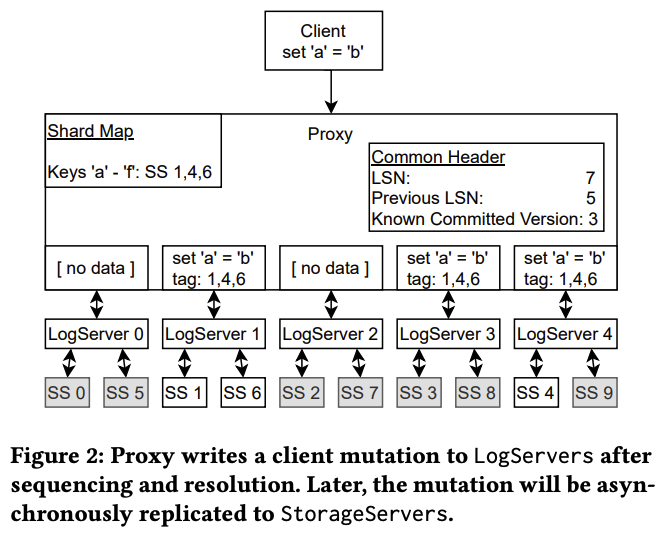

What happens to the logged data? It is asynchronously distributed to storage servers.

The Sequencer assigns a read version and a commit version to each transaction and, for historical reasons, also recruits Proxies, Resolvers, and LogServers. Proxies offer MVCC read versions to clients and orchestrate transaction commits.

When we look at the official architecture diagram, there is more than one resolver, which means they can check conflicts in parallel.

Sharding

So far, I haven't mentioned the sharding system of FDB. This DB uses range-based sharding.

If we have 3 Storage Servers, we can distribute them like 1..10 - 11..20 -

21..30.

The 5-Second Rule (MVCC Window)

MVCC window time is ~5 sec. That means if we have a conflict, it has to be within 5 sec; otherwise, this is going to be rejected due to the 5 sec window time.

- If I have a transaction that is lasting 1 hour, this is going to be rejected.

- If I have a transaction that is lasting 1 hour, on the 6th sec I send a read query, the whole

transaction is going to get

transaction_too_old. - If I have a transaction that is lasting 5 sec, and on the 2nd sec my computer crashed, no worries. As I mentioned, the whole changes were in my client buffer; the server does not care about it, and there was no lock in the server or anything.

In traditional systems, the client has to send ROLLBACK; or other types of check mechanisms (TCP health check, transaction timeout, etc.).

Log Sequence Number (LSN)

The diagram tells so many things; as a reader, I could not quite understand LSN. If there is a WRITE_COMMIT lost, the check mechanism will not allow writing.

WRITE_COMMIT 3 sent

WRITE_COMMIT 5 lost

WRITE_COMMIT 7 sent - not allowed.

Additionally, this keeps ordering between the WRITE_COMMITs. Idempotency is crucial for entire distributed systems, and FDB's nature is distributed.

In many databases, this type of mechanism is implemented like if the database crashed and for self-healing logs have to be rewritten, but unfortunately, this is a so costly process. LSN solves this problem by asking this question itself: "So, where were we?".

RateKeeper and Conflict Scenarios

I talked about OCC before and the retry mechanism. I got a question here, for instance:

for i to 1_000_000 // I exaggerated the number for clarity

FORK_NEW_THREAD

READ A

SET A RAND(1000)

In this case, many transactions will conflict because they READ the same key that others WRITE to. RateKeeper is triggered then, making the transaction start and get read version processes slower. In a highly competitive process environment, FDB performance and throughput are going to be mitigated. Here!

In another scenario:

for i to 1_000_000

FORK_NEW_THREAD

SET A RAND(1000)

This type of transaction is called a blind write. There is not going to be a conflict. RateKeeper is not going to be triggered due to conflicts (since there are no read-write conflicts in blind writes), but may still slow down the system if LogServers or Proxies become overloaded.

Failure Modes: What Happens If...

The Cluster Controller goes down?

Coordinators elect a new ClusterController with disk-based Paxos consensus algorithm; most metadata is stored in StorageServers. Keys start with 0xFF.

The Proxies go down?

Proxies are stateless, so they do not require recovery.

The Sequencer goes down?

If the sequencer fails, the cluster controller detects failure and recruits a new Sequencer. Transactions are forced to be stopped. A recovery process is required.

The Resolver goes down?

If the resolver fails, the cluster controller detects failure and recruits a new Resolver. Transactions are forced to be stopped. A recovery process is required.

The Log Server goes down?

Data is written f+1 synchronously, and during this process, if the log server fails, transactions are forced to be stopped. A recovery process is required.

The Storage Server goes down?

If data is inaccessible, the retry mechanism triggers. The data distributor monitors failures and balances data (based on bytes stored) among StorageServers by moving shards to healthier servers.

Replication Factor?

When I read about it for the first time, I found the f+1 replication factor concept confusing. The overall architecture supports f+1 replication. For example, if we have a replication factor of 3 (f=2), it means we can tolerate the loss of 2 servers without losing data.

Summary

To summarize everything so far:

Maybe I will never have a chance to use this database in production, but on the other hand, I gained valuable insight into database internals. If you profile that heavily relies on LOCKs, you will realize cpu spends significant amount of time acquiring and releasing them. This introduces hidden costs like CPU cache misses and context switching etc. Conceptually Lock-Free structures mitigate these type of overheads. Additionally, MVCC ensures that reads are never blocked by writers when a transaction starts. These terms are not perfect and there are a few sharp angles to keep in mind, but this should be enough for this article.